In aesthetics, there’s this perception of American providers’ being perpetually late to the party—among the last to get their hands on the latest It treatment—due to the famously burdensome approval processes established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). From global counterparts on distant shores, our doctors hear of the hundred-plus dermal fillers available across Europe; the hyaluronic acid (HA) “skin boosters” enjoyed by our glowy-skinned neighbors to the North; the injectable antioxidants and library of threads routinely used to brighten and shape South Korea’s most meticulously cared-for faces.

Some of these innovations are currently in clinical trials in the U.S. and could be coming soon—sooner or later, anyway. Others, we may never see. Aesthetics approvals are so relatively rare here that we tend to celebrate with gusto the greenlighting of every new filler, toxin, or machine before even fully understanding its value—what, if anything, it may add to our existing FDA-approved armamentarium, which boasts dozens of devices, roughly 35 fillers, from a handful of brands, and four neuromodulators.

Charged with ensuring the safety and efficacy of drugs and medical devices in the U.S., the FDA classifies botulinum toxins, like Botox and Dysport, as drugs and fillers—HA varieties and non-HA biostimulatory types—as implantable medical devices, explains Dr. Paul Friedman, a board-certified dermatologist in Houston. Since fillers are considered Class III devices, they’re subject to the most stringent oversight, while other types of devices, like mechanical and energy-based tools, may fall into a lower-risk category that demands less evidence for approval, especially if they’re deemed substantially similar to an already cleared “predicate” device. Non-filler device trials, on the whole, “tend to be smaller than drug trials and are more difficult to blind, randomize, and control,” adds Dr. Friedman.

Interestingly, lasers and other resurfacing, toning, or sculpting devices often originate in the States—Fraxel, CoolSculpting, and Ellacor micro-coring, for example, were all invented in Boston—so we commonly gain access to top-tier devices before the rest of the world.

For neuromodulators and fillers to achieve FDA approval, they must undergo a rigorous process involving at least three phases of clinical trials to assess safety and efficacy, each of which takes approximately one to four years to complete. Once these standard trials wrap, the FDA must review the data, which can also take months to years. Additionally, “Phase IV post-approval clinical trials may be mandated by the FDA, for ongoing surveillance of safety and other effects—and these can last years, even up to 10 years,” explains Dr. Hema Sundaram, a board-certified dermatologist in Fairfax, Virginia, and Rockville, Maryland, and a regulatory advisor in North America, Europe, and Asia.

As part of FDA review, “manufacturing facilities and the entire manufacturing process must also undergo inspection,” Dr. Sundaram notes—which isn’t always a slam-dunk situation.

Revance, the maker of a neuromodulator called DAXI (DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection)—shown in trials to freeze frown lines for a good six months—was dealt a major surprise, in the fall of 2021, when the FDA rejected the drug due to certain “manufacturing deficiencies.” This could delay its approval for at least another several months. While DAXI is not yet approved for use anywhere in the world, the American aesthetics community had quietly been predicting a late 2021 launch.

All in all, the FDA approval process is “truly a labor of love,” Dr. Sundaram adds. “As an FDA principal investigator myself, I know firsthand how many thousands of hours my study team and I spend on conducting clinical trials and the associated responsibilities, including monitoring visits by the research organizations that independently oversee the trials as well as interfacing with the Institutional Review Boards that ensure ethical study conduct and treatment of study subjects.”

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the world…

Other countries have their own regulatory bodies and protocols. In Europe, the approval process for drugs, like neuromodulators, is reportedly as painstaking as ours. (And despite what you may have heard about the FDA’s sluggish pace, studies have actually found that drugs are frequently approved and brought to market faster in the U.S. than in the European Union or Canada.) Devices, including fillers, tend to be handled differently abroad. For starters, “in the U.S., a device must demonstrate both safety and efficacy for FDA approval,” Dr. Friedman tells us. Whereas in Europe, “a device must demonstrate safety and performance—as in, it performs as designed—but it’s not required to show clinical efficacy.”

Approval guidelines in Europe are presently being revamped—more on that in a bit—but historically, for a filler to be sold in Europe, it had to have what’s called a CE (conformité européenne) mark. Rather than a central authority parsing trial data and granting approvals, however, device applications have long been reviewed by a “notified body” (NB), or a private company that supplies certifications for a fee, explains Dr. Friedman.

In a 2016 paper comparing European and American approval processes, Dr. Gail A. Van Norman, a professor in the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, states that “although the CE mark is often mistakenly equated to being a seal of quality, in fact, achieving a CE mark merely indicates that the device in question is in full compliance with European legislation.” The author goes on to explain how standards differ among NBs, with some being far less fastidious than others.

“The CE mark does not indicate scientific quality,” bemoans Dr. Jonquille Chantrey, an aesthetic physician in London. “CE-mark approval may take 4 to 16 weeks—the process is far faster than approval for a drug in the U.K., as there are fewer medical restrictions and requirements.” While botulinum toxins are treated like prescription drugs in the U.K. and appropriately scrutinized, she says, “the majority of cosmetic injectables available here are medical devices and do not need to go through clinical trials and scientific safety licensing.”

Dr. Sundaram highlights another critical difference between FDA approval and CE marks. In the U.S., a filler or neurotoxin can make its way to injectors only after “several phases of full clinical trials [have been] run on the actual product, with stringent analysis of data, to determine safety and efficacy for a specific product indication.” In Europe, on the other hand, CE marks have customarily been awarded “through submission of published data for already existing equivalent products plus post-marketing clinical follow-up after CE marking is obtained,” Dr. Sundaram explains. What this means, she adds, is that a product’s “side effects may only come to light post-approval, after a large number of patients have already been treated.”

Back on our side of the pond, Canadian physicians also see certain injectables before American doctors. In many cases, this is because “the clinical trials were started earlier in Canada and hence the data was submitted sooner,” Dr. Sundaram points out. What’s more, unlike the FDA, which requires evidence from U.S.-specific clinical trials, Canada’s regulatory agency (Health Canada) is willing to accept data from other countries, notes Dr. Katie Beleznay, a board-certified dermatologist in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Likewise, “some non-European countries, like Hong Kong, will automatically approve a product for use if it has CE marking,” says Dr. Sundaram. In Mexico, devices that are cleared in the U.S. or Canada are similarly fast-tracked and need only get technical documents translated into Spanish and notarized, according to a 2017 study on global device-approval practices.

The global game changers doctors are buzzing about

“Skin boosters,” aka injectable hydrators

When a product gets OK’d abroad years before passing muster with the FDA, American providers happily benefit from the trial-and-error experiences of their peers. Of all the injectables flowing around the world, a group of HAs dubbed “skin boosters”—ultrafine gels, like Juvéderm Volite and Restylane Vital, which are injected superficially into the dermis, across broad areas, to smooth and hydrate the skin—are probably most coveted by American injectors because they can give effects that traditional volumizing fillers cannot. Profhilo is another standout: this HA, uniquely free of the crosslinking chemical BDDE, stimulates collagen and elastin growth while blurring fine lines and remaining undetectable even under thin skin, like that of the neck.

“Skin boosters have really risen in popularity since the days when Profhilo came on the market,” says Dr. Ashwin Soni, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Surrey and Berkshire, England. “Now there are several filler companies developing these hydrating and skin remodeling injections—Teoxane Redensity 1 and Belotero Revive are gaining popularity here—in order to improve skin health and create that beautiful glow that patients desire.”

An innovative breast implant

In the surgical realm, new approvals can breed novel ideas—and sometimes even revolutionize a doctor’s operative approach. According to Dr. Jamil Ahmad, a board-certified plastic surgeon in Mississauga, Ontario, Allergan’s Inspira breast implants—which he describes as “optimally filled cohesive gel implants”—launched in Canada several years before earning FDA approval in the States. In that time, he discovered that the shell on these smooth, round implants was less prone to collapse and rippling compared to other devices he’d used previously. This allowed him to perform “a lot of subfascial breast augmentations, even in quite thin patients with minimal breast tissue,” he says—thereby skirting “some of the aesthetic disadvantages of going under the muscle,” like animation deformity (the implant flattening or moving down and out when the pectoral muscle flexes) and “double bubble,” which appears as a crease above the breast fold, says Dr. Ahmad, and develops due to “a disharmony between the ligaments within the breast and the muscle window-shading up” when it’s cut during surgery.

“These may not be the newest things approved here, relative to the U.S.,” says Dr. Ahmad, “but they are the things we should be talking about in terms of giving more options to patients, many of whom get dual-plane [under-the-muscle breast augmentations] without any discussion.”

Skin tightening devices

While Dr. Ahmad shares his experiences globally through lectures and studies, he admits to being similarly informed and influenced by the firsthand accounts of his colleagues abroad. Only in the past year or so has he adopted Morpheus8 and BodyTite, two radiofrequency-based skin tightening technologies from InMode, both hugely popular in the U.S. “They’ve been around far longer in the U.S. but are just starting to catch interest in Canada,” he says—thanks, in large part, to U.S. doctors posting about the devices on social media. Dr. Ahmad uses Morpheus8 for both facial resurfacing and to tighten crepey skin on the abdomen, thighs, and calves. BodyTite, he pairs with liposuction, particularly when contouring the flanks and neck, to help the defatted skin contract a bit more than it does with lipo alone.

Sculptra

The world also looks to America for insights on Sculptra, the poly-L-lactic acid suspension that gradually revolumizes skin by stimulating collagen production. While the injectable has been FDA approved for cosmetic use since 2009—and for facial wasting associated with HIV since 2004—plastic surgeon Dr. Rosalia Luketina says it’s launching only now in her Zurich clinic. In Munich, board-certified dermatologist Dr. Timm Golueke has been using Sculptra in the face for years but has recently seen an increased demand for buttocks and abdomen injections. “Clearance for body treatments is still pending, but a lot of colleagues are using it off label,” he says. It’s a similar story in America, where Sculptra is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of cellulite of the buttocks and thighs.

Regulatory changes underway

After years of swift clearances based on minimal testing, European regulators are now aiming to align their approval processes with those of the FDA.

The impetus for change actually dates back decades, to when the European Union’s systemic shortcomings were exposed by the PIP breast implant scandal. To simplify, the French implants were denied FDA approval but did acquire a CE mark in the mid-1990s and were widely used throughout Europe, the U.K., Brazil, and Latin America. “In 2001, PIP started making and selling implants that contained unapproved, cheaper, industrial-grade silicone rather than the medical-grade silicone for which they had been authorized,” says Dr. Sundaram—a fraudulent move that led to an excessively high rate of rupture. The implants were removed from the market in 2010 and have been linked to several cases of breast cancer and toxicity-related deaths.

This incident set in motion a dramatic, yearslong overhaul of European device regulations, the implications of which are only now beginning to take effect. Going forward, “manufacturers of fillers and other implants plus lasers and IPL will face more stringent requirements for safety, product performance, and quality control,” Dr. Sundaram tells us. As a result, “we can expect new fillers to take significantly longer to achieve CE marking.”

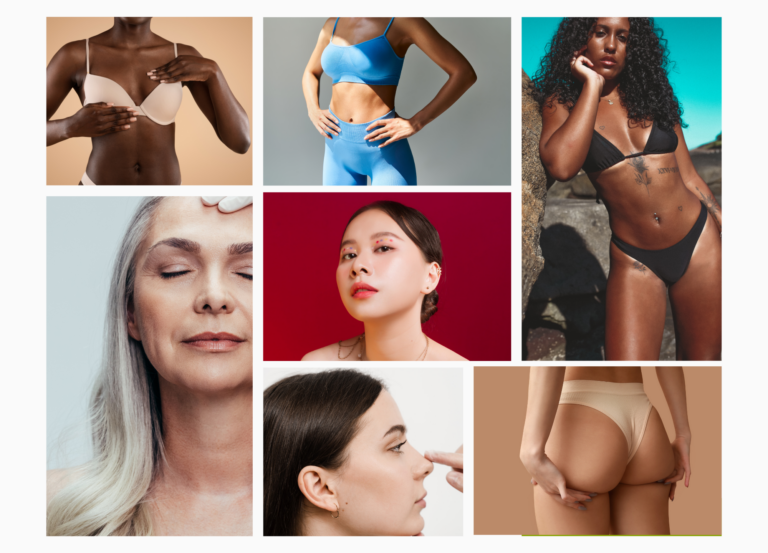

American investigators are seeing approval paradigms evolve here at home as well. While dark skin types have traditionally been underrepresented in aesthetics clinical trials, more recent “FDA studies of neuromodulators and fillers tend to require a diverse subject population, with a certain percentage of patients of color, [to ensure] data reflects the real-world patient population in which the product will ultimately be used,” Dr. Sundaram says. This overdue change, coupled with updates abroad, should make our proverbial beauty party a safer, more inclusive event.