Here’s a truism about surgery: it will most likely leave you in stitches.

Their purpose is singular, says Dr. Laurie Casas, a board-certified plastic surgeon in Chicago. “Sutures help hold the wound together while collagen is deposited so you have closure and a barely visible scar.”

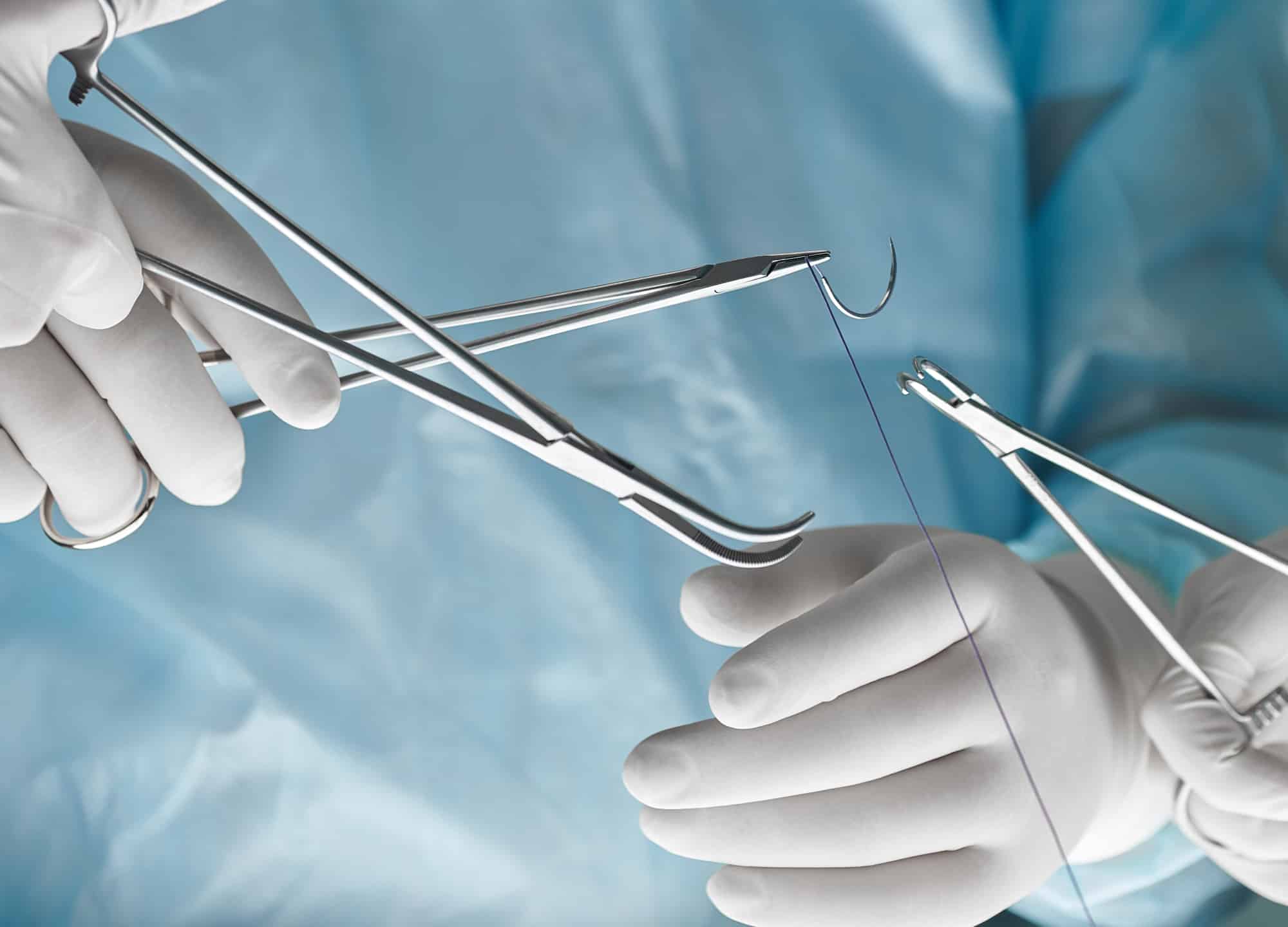

In the grand scheme of going under the knife, how your surgeon sews you back together may not get a lot of consideration. But when it comes to having a nice, as-close-to-invisible-as-possible scar, stitches—from the type of material used to when they’re removed—can play a significant role. “Closing a wound may not be the most creative part of plastic surgery, but to patients, the scar is one of the most important things,” says Dr. Casas.

This makes it a good idea to know how your surgeon is going to stitch you up after surgery.

1. There are two kinds of sutures.

Sutures can be either absorbable (aka dissolvable), which means they lose the majority of their tensile strength within 60 days, or nonabsorbable. Absorbable sutures are generally used as deep sutures; they dissolve on their own and don’t need to be removed. Nonabsorbable sutures, which are either permanent or require manual removal, are typically used as surface sutures—meaning they’re on the outside and you can see them.

As a prospective patient, the key fact about suture material that you need to know is this: while using absorbable stitches can avoid the inconvenience and possible discomfort of suture removal (more on this later), absorbable stitches dissolve through a process called hydrolysis, during which your body breaks down the suture by causing inflammation. “The amount of inflammation is so much that it’s not a good way to suture a cosmetically important area, like the face,” says Dr. Ariel Ostad, a board-certified dermatologic surgeon in New York City. “Yes, maybe the patient doesn’t need to come back to have their stitches removed, but from a cosmetic standpoint, it’s going to lead to a lot of redness and inflammation and potential scarring on its own.”

Especially on the face but, really, anywhere that you want to avoid months or even years of healing time, it’s best to use stitches that are nonreactive, like nylon ones, and removed—a process that usually causes little to no discomfort. If you’re super-nervous about having your stitches removed or have a low tolerance for pain, ask your surgeon to prescribe something to calm you down or arrive early to receive a tiny amount of numbing cream. Holding a vibrating device, to distract your brain, may also help.

If you’re wondering about using tissue glue to get around having stitches at all, it’s usually not a viable option. Most plastic and dermatologic surgeons prefer to suture skin edges together, since it produces a more precise result. For aesthetic procedures, surgical adhesive—a medical version of Crazy Glue—is typically used as an adjunct, for instance, to seal the top layer of skin after a tummy tuck.

2. The deeper stitches are the ones that really matter.

It may seem counterintuitive, since they don’t show, but the critical step in suturing correctly has to do with putting in adequate deep stitches, those below the skin, so there’s no separation between your skin edges. When put in properly, these stitches are what help create a scar that’s a fine line. “These stitches pull the skin together from the bottom, to reduce tension,” says Dr. Ostad. “When the skin is properly stitched so that it’s juxtaposed and opposed beautifully, you’re not even relying much on your top stitches to hold the skin together—they’re more there for insurance.”

Depending on the procedure, two layers of sutures may be used to close an incision, which is known as a bilayer closure. In others, for instance, in areas of high tension, such as a tummy tuck, breast reduction, or breast lift, three or more layers may be used. This can tack extra time onto the procedure, but it guarantees you the best chance at a perfect scar. So don’t be afraid to ask providers you meet with about their suturing technique.

While you’re at it, inquire as to whether a surgeon personally does or supervises the closing—so it’s being done the way they want it, Dr. Casas suggests. “It isn’t critical that the primary surgeon places every suture, but it is critical that the assistant who’s tasked with placing sutures does it the same way they would.”

3. When it comes to removing stitches, timing is everything.

If stitches aren’t removed before the top layer of skin heals around them, the entry points of the stitches may become permanent features, resulting in a “railroad scar.”

In most cases, surface sutures of any kind are removed after no more than five to six days.

If your surgeon tells you to wait longer to have your stitches removed, something that—based on RealSelf member questions—happens too frequently, be sure to ask why. Stitches left in place much longer are a major risk factor for a poor final scar with visible suture marks.

In areas of high tension, such as the torso, back, chest, and abdomen, where stitches need to be left in longer than a week, there’s an advanced method of suturing, called a running subcuticular stitch, that avoids any external stitches—and any unsightly track marks. “The stitches are snaked completely under the skin from one end of the wound,” explains Dr. Ostad. “They make the skin strong without producing any additional scarring.” These stitches can be pulled out after two to three weeks or used with what’s called a Monocryl suture, a nonreactive filament that dissolves on its own.

4. Sutures like to “spit out.”

It’s not uncommon at about the six-week mark for sutures that are buried deep in the skin to work their way to the surface and start poking out. These so-called “spitting” sutures are more common with permanent sutures, which is why some surgeons don’t like to use them, but they can also occur with dissolvable sutures.

Spitting sutures usually appear like a little red bump or pimple with some discharge along your suture line; you may feel but not see the offending thread sticking out. Though annoying and sometimes distressing (patients often worry there’s an infection, says Dr. Ostad), spitting sutures aren’t a big deal—they typically don’t affect long-term healing or scarring. (Keep in mind too that with many cosmetic procedures, a spitting stitch is probably just one of the sometimes 100 stitches that you don’t see.)

Applying a warm, moist compress to the inflamed area for a few days may help expose more of the suture, which can then be trimmed with a nail clipper. If it doesn’t go away or seems to be getting worse, see your doctor so they can remove the suture in a sterile fashion, to avoid an infection.

5. Just because your stitches are removed doesn’t mean your skin is healed.

Surgical incisions can be likened to an iceberg: Much of what’s going on is happening under the surface. Even though the skin’s surface may look like it’s healed, the skin—especially the deep stitches underneath—is still quite fragile. “The strength of the skin at about the two-week mark is 10% of the strength that skin had prior to surgery,” explains Dr. Ostad.

The upshot: if you jump or move around too much, you can undo some of the deep sutures and loosen the superficial ones, allowing the wound to reopen or—due to the sutures’ gradual loss of tensile strength—the incision to pull apart and the scar to seperate and widen. “All of a sudden, that line is wider and the patient is asking, ‘Why do I have a worm instead of a fine line?’” says Dr. Casas.

Areas that are under a lot of tension, like the back, shoulders, and abdomen, are most prone to widened scars. “It’s a challenge, because people are active,” says Dr. Ostad. “But I tell patients that if the scar matters to you, you want to avoid strenuous activity,—ideally, for a good six weeks.”