I have my father’s nose, and I resented him for it my entire adult life. Both of my parents have big noses, but at least my mother’s is straight. When I was a kid, she would pinch my nose and count, “1, 2, 3, 4, 5.” When I asked why she did that, she said to stop my nose from growing. I knew, even at 3 or 4 years old, that a large nose was an undesirable trait. I am the child of two Jewish Moroccans who met after immigrating to Los Angeles. All of my aunts and uncles had married and procreated with fair-skinned, blonde, blue-eyed Americans. My Moroccan family would ooh and aah over my golden-haired cousins; they could not resist the novelty of it, photos of them were all over the grandparents’ house, and I simply did not exist.

I spent a long time trying to find out where I fit in growing up, while also trying to separate myself from the roots that brought me no favor. I often switched styles and reinvented myself: black lipstick, a full head of braids with bright orange extensions… the more shocking, the better. Looking back, it’s obvious how desperately I wanted to be noticed. I wish I could go back and tell that girl that she was perfect and didn’t need to try so hard—that their lack of approval had nothing to do with me.

Aside from being insecure about my appearance, it’s fair to say that I had talent. I sang and danced, and I could make a room laugh and hold people’s attention. So I decided at a young age that I would be an entertainer. And if I was going to be an entertainer, I knew that I would get a nose job. This was simply the unspoken cost of entry. Very few of the successful women (or even men) I saw on-screen had big noses, and if they did, they were never the romantic lead. Sometimes they would get lucky enough to play the sidekick or the Jewish girl. Barbara Streisand, Anjelica Huston, Meryl Streep, and Bette Midler are exceptions to the rule, and none of them were ever recognized as great beauties, always as brilliant “character” actors.

I wanted to be beautiful, so I needed a nose job… and the money for one. Rhinoplasty isn’t cheap if you want it done right, and I knew better than to go cheap on my face. At 20 years old, I was a young waitress/actress who often struggled to pay my half of the $1,200 rent, so it was hard to imagine how I’d afford a five-figure surgery, but I booked a consultation with a plastic surgeon anyway.

There, the doctor told me that I had a deviated septum and that I could get that part of the surgery covered by insurance (which I didn’t have then either) while he “fixed the rest of my nose” simultaneously. I would have been more offended by the phrasing if I hadn’t already internalized that this was something I desperately needed to “make it,” both in my career and in life. Any time a relationship didn’t work out, I couldn’t help but think if only I had a smaller nose, they would have loved me. This surgery would make me somebody, and it would make me worthy of lasting love. But I still couldn’t afford it, so I had to wait.

Fast forward to eight years later. I was still acting on the side but had also begun to cook and was growing a presence as a food influencer on Instagram and YouTube. I booked a job as the personal chef for an Academy Award-winning actor. I turned that into a food media agency where I developed content for national chains and Michelin-starred chefs. I made more money than I ever had, which allowed me to begin researching surgeons again. Unlike the first time, Instagram was now available, and I could spend hours a day looking at before-and-afters of nose transformations. After what some might consider an obsessive amount of research, I kept returning to one surgeon: Dr. Richard Zoumalan, a board-certified facial plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills, California.

I booked my first consultation with him for October 8th, 2018. That day, I informed a friend about my exciting news, and he protested. I was upset: I shouldn’t be shamed for wanting to do something that would make me feel better about myself, something that most women who were considered beautiful in Hollywood have done in secret. He apologized, then asked, “If you weren’t from L.A, do you think you would still think anything was wrong with your nose?” It’s true—I was suffering from a cultural issue, but was I really to blame for being a product of my environment? I chose to go ahead with my plan, but his question always stuck with me.

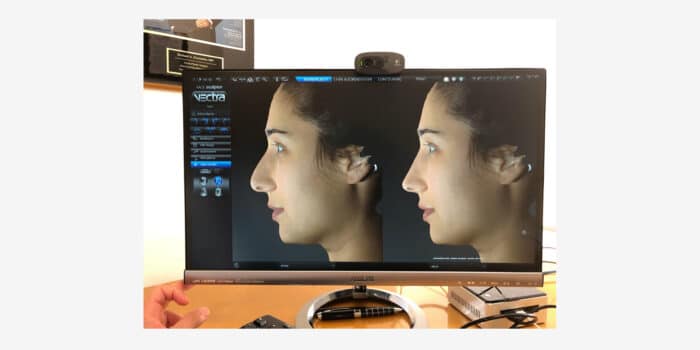

My best friend accompanied me to my consultation. She knew I had wanted this forever and wanted to make sure I didn’t get manipulated by some skeezy surgeon. Dr. Zoumalan was anything but. To my surprise, he tried to dissuade me from rhinoplasty, saying that, in his opinion, I wasn’t unhappy enough with my nose and that I would likely be unsatisfied with the results of any surgery. I had actually liked my nose in the photos he took, except in the 3D image (that thing makes everyone look hideous). While he showed me on a monitor what I might look like after surgery, I winced and shrieked in horror as he digitally adjusted my nose. “That’s way too small!” I exclaimed. “Can you make it a little bigger?” He explained that he had a specific style and that, in his experience, women didn’t like it when their results were too subtle. He allowed me to go home with a picture of my mock-up and think it over. I left his office confused about the feeling of relief I was experiencing.

The next morning, I woke up feeling renewed, with a newfound feeling of love and acceptance for my nose. While in bed, I pulled out my phone and proclaimed to the world (my IG Story) that it wasn’t me who needed to change, it was society’s rigid beauty standards. “Make big noses beautiful! All women shouldn’t have to look the same to be considered beautiful!” I wish I could say that feeling lasted, but after a few months, the thoughts started to creep back in, more intensely than before. It is very likely I have some version of dysmorphia. The thoughts about my perceived flaws can sometimes become so invasive that it is difficult for me to appreciate my life. A bad picture can send me into a spiral that causes me to self-isolate and ruminate on how hideous I am for hours. It’s emotionally draining and feels painful and pathetic.

Ultimately, I couldn’t take it anymore. I wanted to think about something else and thought that if I got the nose job, it would free my mind to focus on other things. So I decided to go back to Dr. Zoumalan for a second consultation. He didn’t charge me for my second consultation, and he listened patiently to my concerns, but again, I left unsure. Although he was great, I thought it was crazy to speak with only one surgeon. I decided to reach out to another doctor, whose work seemed a bit more subtle and less “perfect.” The receptionist informed me that the next appointment was in nine months, so I booked it.

Then one night, I was watching a Netflix show called Explained. There was an episode, titled “Plastic Surgery,” that I assumed would be a commentary on how modern celebrities like the Kardashians affected beauty standards, but instead, it began right after World War I. Soldiers had returned from war horribly disfigured, and plastic surgery was invented to help them regain some sense of who they once were. One of those innovative surgeons was named Dr. J. Joseph, and he is now known as one of the fathers of aesthetic surgery, specifically for his work with noses. As the narrator tells it, “Joseph was Jewish-—and so were many of his patients, who wanted him to erase the markers of their ethnicity, allowing them to be inconspicuous in a society that was hostile towards them.” I began to cry when I heard that and saw the images of some of the first nose job before-and-afters. It broke me to learn that the procedure I had been pining for most of my life was originally developed to help my ancestors camouflage themselves for safety and access to opportunity in society. The unspoken cost of entry.

After that, something shifted in how I looked at the before-and-afters in my Instagram feed. I started to become horrified by the majority of the after photos; I would feel an actual jolt in my stomach and question what was wrong with the initial nose. It was a dramatic change in taste that caught me off guard. Perhaps it was the result of the history lesson or the vast quantity of these images and videos I had seen. I began to notice that thousands of women were being made to look a specific way, and I started wondering how indicative of the final results some of the initial reveal videos really were.

Recently, I went down a dark hole on TikTok after clicking on the hashtag #nosejobcheck. The trend begins with a young woman covering her nose. The audio says “nose job check,” followed by music, and the user inserts a series of videos of them turning their heads to the beat, first with videos of their original nose, then clips from after the surgery with the bandage on, and finally the reveal of their new nose. At the time that I am writing this story, that hashtag has 2.4 billion views on TikTok. (In comparison, the hashtag #dancetrend—arguably the reason TikTok exists—has 2.2 billion views.) After watching more of these than I care to admit, it became clear to me that the chances of a bad result were probably higher than surgeons lead us to believe. I didn’t want that to happen to me; my mental health would not survive it.

I soon stumbled across another hashtag: #ethnicnosejob. There, I found a particular group of women who looked like me. Many of them were Jewish or of Middle Eastern descent, with similar facial features to mine, and they were erasing the features that set them apart. I remembered my friends telling me, “Your nose is what makes you unique” and “it fits your face perfectly”—statements I had filed away as polite lies at the time. But I thought those same things about the women in these videos, and I began to feel sick. Then I searched one more hashtag: #ethnicnose. Here I found a small group of women who had begun to post videos showing their ethnic nose with pride. One that stood out was made by @noornavaid, who looked like a queen to me. I watched as many of these as possible; they were quite literally healing me.

@azohrable I bet money big noses become all of the rage. #ethnicnose #ethnicnosechallenge #ethnicnosetrend #nosejob #ethnicnoses❤️❤️🥰😘 #ethnicitychallenge #ethniclook #ethnicnose ♬ original sound – 959pm on ig

That is the power of representation—seeing yourself reflected back to you as beautiful is a remedy for self-loathing. Out of gratitude, I decided to contribute to the trend. The videos had helped me, and if I could help even one other person, I wanted to. I had only made a handful of TikToks at the time, and I had no way of knowing this one would go viral. I took a clip showing off both sides of my profile and wrote, “I’m so glad I held off on getting a nose job. My ethnic nose is what makes my face unique. It’s chic and sophisticated. No surgeon can create this. I have a feeling big noses are about to be the fashion. This is what happens when something becomes rare.” I posted it and went to work.

When my catering gig was over and I looked at my phone, the TikTok had 7,000 views. I had 22 followers at the time, so I was impressed. Less than an hour later, the views had doubled. I found it odd—this was perhaps the least creative piece of content I had ever made, yet it was taking off. I refreshed the notifications a few times in a row to see what would happen, and it would jump by 50 to 100 views every time. I guess I wasn’t the only one who needed to see this kind of content.

There are thousands of words of encouragement, compliments on my nose and face, and thank-yous on my video. “I finally found the right side of TikTok,” some commented. Others even admitted that they regretted their nose jobs and missed their old nose. My favorites? “I just canceled my consultation” and “because of videos like this, I like my nose.” The video now has upward of 1 million views. It’s a surreal experience, affecting that many people. I’m not magically fixed now; I still have days when I think I look like shit, but I have embraced my features as they are—a representation of my ancestry and an intrinsic part of who I am. I have zero judgment on what anyone else decides to do to their face or body. Everyone is just doing their best to feel good in their skin, and I fully support whatever safe road gets you to that point, but I’m grateful that this was my journey.